Is Carbon Capture and Storage a more inclusive and human-rights based, sustainable way to lessen carbon emissions, than robustly restricting carbon based fuels and activities, as the world changes its fossil fuel dependence to more climate-friendly forms of energy?

Mary Otto-Chang HBA, MES, PhD Candidate

September 2022

Introduction

There is much discussion about the role of carbon in our changing climate. The current guiding principle within climate change circles, is that by constricting carbon emissions, by restricting carbon use, the climate will, in time, regain its natural balance. Although of benefit to the planet’s overall ecological platform of all life, carbon restrictions have massive socio-economic and cultural impacts, some of which are vernacularly known as “first world problems”, but many of which are negative, not only for carbon-based energy related global production and associated economies, but also for much of the world’s less advantaged populations.

One ponders is there not a more human-rights based way to lessen carbon emissions, while the world changes its fossil fuel dependence to more climate-friendly energy forms? Can the timeline of climate change be extended, while working with socio-economic goals simultaneously?

Apart from governments, intergovernmental structures, international economic bodies and financial institutions shying away from many alternative energy forms and technologies, which they duly excuse because of the massive infrastructure already in place for fossil fuels, another way of decreasing carbon emissions and levels in the atmosphere is to remove it, and store it or use it as a resource. This is known as Carbon Sequestration (CS) or Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS), and this paper examines how much potential this lesser known soldier has, and why it has not been well promoted by those responsible for national and global public policy.

The premise of this paper, is that although carbon sequestration is technically a key player in avoiding catastrophic climate change, the crevasse of interests in the current fossil fuel and nuclear energy infrastructure, along with associated and other economic and political interests, have largely protected these industries, have given only token support to the various forms of clean energy, generally ignored many free energy technologies and provided mainly lip service and alms for the development and employment of carbon sequestration. Importantly, this paper also investigates the main past and present drivers of decision making in international climate arenas. As such, today’s nearing of a climate crisis, could have been greatly buffered, and the negative socio-economic impact of carbon restriction largely avoided, if, along with its corollary of cleaner energies, carbon sequestration technologies had been focused upon in the recognized official repertoire of global sustainable development conversations, decades ago.

An Imbalanced Atmosphere

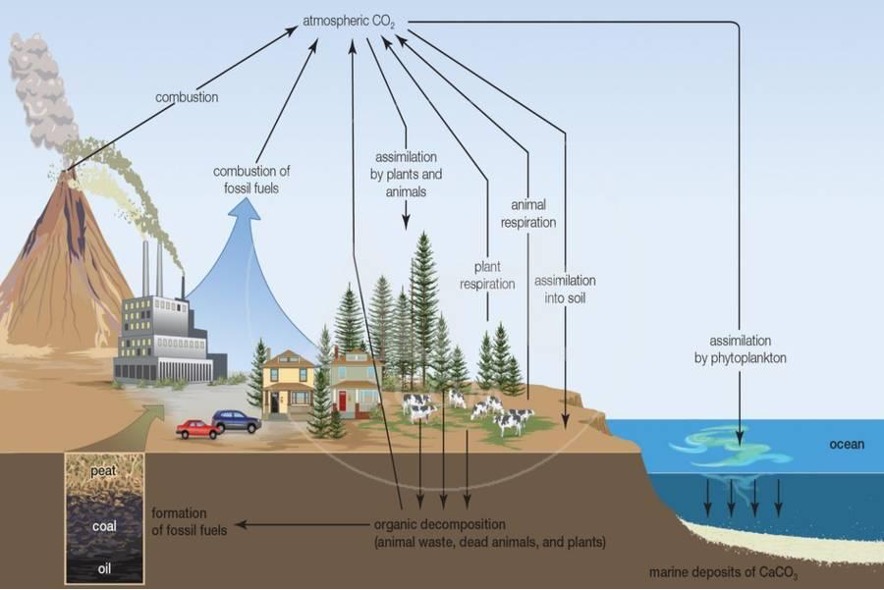

Carbon is life. Carbon, a chemical element, is a fundamental building block of biomolecules. It exists in solid, dissolved, and gaseous forms. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a gas that is produced naturally in the biosphere and is also generated from various human activates. Man-made carbon dioxide is generated by human activities such as burning fossil fuels and biomass, such as wood, dung, peat, coal, natural gas, petroleum products, amongst others. Decomposing organic matter, forest fires, volcanic activities and other naturally occurring land use changes can all produce biologically originated CO₂. Please refer to Diagram 1.

Diagram 1: The Carbon Cycle (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2008)

In the mid to late 1800’s, experimental studies were undertaken suggesting that human-produced carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other gases could accumulate in the atmosphere and similar to a greenhouse, actually insulate the Earth. Decades later, CO₂ readings would provide some of the first data to support the global warming theory by the late 1950’s. In the following years, evidence continued to consistently reflect that CO₂ and other “greenhouse gases (GHG) namely, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and ozone in the lower atmosphere that accumulate in the atmosphere can trap heat and contribute to climate change.”1 By the late 1980’s, and into the 1990’s, global attention to global warming had resulted from an abundance of data, along with climate modeling and real-world weather events, clearly demonstrating that not only was global warming real, in part man-made, but that it also had many associated impacts and potentially disastrous consequences.

Custodians of Climate Change

Without detailing the changes within the global institutional framework, a holistic understanding of global climate governance cannot be reached. As such, subsequent technical discussions arise within an informed context.

In 1988, the UN established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Its task, was to “prepare a comprehensive review and recommendations with respect to the state of knowledge of the science of climate change; the social and economic impact of climate change, and potential response strategies and elements for inclusion in a possible future international convention on climate.” 2 In 1990, as the first IPCC Assessment Report was published, international fora finally had the scientifically and collaboratively driven and formally recognized evidence needed to proceed. The 1992 Earth Summit lay the groundwork for the UN Framework for the Convention of Climate Change (UNFCCC) which was created as an overarching legal framework guiding the annual meetings of its working body, the Conference of the Parties (COP). In 1994, UNFCCC was operational and in 1995, in Berlin, Germany, COP 1 was held.

Consequently, legacies of hours, amongst the thousands of COP participants, backed by IPCC’s scientific findings, along with efforts from literally countless organizations from civil society and NGO’s, academia, and other scientific and private sector bodies, have resulted in the Paris Accord. The Paris Accord, also known as the Paris Agreement, is a landmark event in addressing climate change. It is a legally binding international treaty, which was adopted by 196 Parties at COP 21 in Paris, in 2015, entering into force in 2016. To achieve the Accord’s main long term goal, which is to limit global warming to well below two degrees Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels, countries plan to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible in order to achieve atmospheric balance in GHG’s by 2050. “The Paris Agreement is…, a binding agreement which brings all nations into a common cause to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects.” 3

Since 2015, significant changes, in terms of the global custodians of climate change – and of sustainable development also – have occurred. Although the UN and partner entities have collaborated with private sector organizations for decades to varying degrees, including the establishment of the UN Office for Partnerships4 and the UN Global Compact,5 amongst many other efforts, June 2019, marked the beginning of a full working partnership between the United Nations and the World Economic Forum towards the UN’s Agenda 2030, which acts as an overarching umbrella of the globally derived at Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s), which are overseen by the UN. Importantly the UN/WEF Partnership Agreement states that there will also be “collaboration between the UN and Forum to meet the needs of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.”6 Prior to this new public/private sector international governance structure, the global climate dialogue and negotiations were undertaken within a solely intergovernmental arena, advised by a highly recognized science and academic community, supported by the regular bilateral and multilateral donor communities, regular international financial institutions, and associated funds established with member state knowledge and democratically voted upon agreement, with all deliberations understood to be fully recorded and fully transparent. Although this new merger gives the long needed financial backing to address climate change, which has always been sorely lacking, the decision making authority has also been changed. As King Charles III, then Prince Charles, poignantly proclaimed at the Convention of Parties (COP 26), Glasgow, 2021, “We also know that countries… simply cannot afford to go green. Here we need a vast military style campaign to marshal the strength of the global private sector, with trillions at its disposal far beyond global GDP, and with the greatest respect, beyond even the governments of the world’s leaders.” 7 Although the new architecture of the global governance landscape has largely gone unnoticed by the masses, many who are aware, remain most concerned about this highest level of formal global collaboration between the world of money and the world of power. The fact that the WEF, founded in 1971, now has literally hundreds of alumni from its Young Global Leaders8 program situated in key governmental posts, along with thousands more in their ongoing leadership programs as well as in top private sector positions, further separates things from the ideals and tenets of transparent democratic governance. Changes within the UN System, along with a multitude of new structures and processes, acting mainly as bridging mechanisms are already established and enable this new global level public/private partnership.

Harris Gleckman, PhD, former head of the NY office of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development states, “This strategic agreement is a coup for the corporate leaders at Davos, but what does it offer the UN and the international community? This gives some of the most controversial corporations unprecedented access to the heart of the UN, yet it has not even been properly discussed by the UN’s country members and certainly not by the broader public.”9 Furthermore, the International Network for Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, highly condemned the UN/WEF partnership, sending an open letter to the UN Secretary General Mr. António Guterres, expressing deep concerns, stating “This is a form of corporate capture, which will seriously undermine the mandate of the UN as well as the independence, impartiality and effectiveness of this multilateral body, particularly in relation to the protection and promotion of human rights.”10 Highly recognized Food First Information and Action Network (FIAN), wrote another open letter, endorsed by over 300 established NGO’s worldwide, stated “The UN’s acceptance of this partnership agreement moves the world toward WEF’s aspirations for multistakeholderism becoming the effective replacement of multilateralism.” 11 It continues, proclaiming the “WEF in their 2010 The Global Redesign Initiative argued that the first step toward their global governance vision is ‘to redefine the international system as constituting a wider, multifaceted system of global cooperation in which intergovernmental legal frameworks and institutions are embedded as a core, but not the sole and sometimes not the most crucial, component.” 12 Gonzalo Berrón, PhD, Associate Fellow, of the Amsterdam based, Transnational Institute, remarked in yet another open letter “This agreement between the UN and WEF formalises a disturbing corporate capture of the UN. It moves the world dangerously towards a privatized and undemocratic global governance” 13.

Whether by design or default, the outcome remains the same and that is the weakening of the role of states in global decision-making, along with elevating the role of a new group of ‘stakeholders’, and thus turning the conventional, and democratically derived multilateral system into a multistakeholder system, in which private sector entities are not only part of, but also by far the most powerful players, within these new governing mechanisms. This is a contextual reality underlying and affecting all decision making within the international climate change arena and as such, is foundational understanding to any related discussions.

The Cognitive Dissonance between Expressed Priorities and Expenditure

When looking at the levels of governmental / multilateral financial support for addressing climate change since the issue was recognized to be of global concern and of potential dire consequences for ecosystem balance and for humankind, in the early 90’s, one soon realizes that these funds have amounted to paltry crumbs from the world’s picnic table.

The Annual 2020-2021 UNFCCC total integrated budget was EUR 169.5 million. 14 This includes the upwards of EUR 70 million on activities of the Convention of Parties (COP), which could be argued as the most important global annual meeting. 15

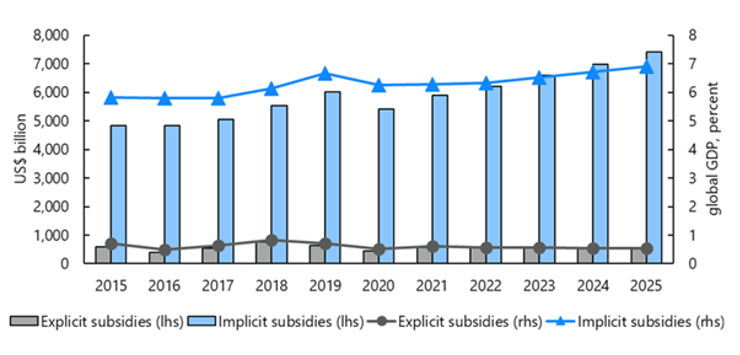

In stark contrast, and reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), “Globally, fossil fuel subsidies were $5.9 trillion or 6.8 percent of world’s GDP in 2020 and are expected to increase to 7.4 percent of GDP in 2025.”16 And yet also in 2020, Bloomberg reported that “the world spent a record $501.3 billion in 2020 on renewable power, electric vehicles and other technologies to cut the global energy system’s dependence on fossil fuels”.17 With mathematics like this, where there is approximately twelve times more spent on fossil fuels subsidies than on investing in cleaner energy, trends will have trouble reversing. Please refer to Graph 1.

Graph 1: Explicit and Implicit Fossil Fuel Subsidies – Global. Source: IMF 202218

Global public and private investment in ocean/tidal energy totaled only €70m ($75.5m) in 2021, which was a 50% increase on the year before, according to an Ocean Energy Europe report”19 It is interesting, that 2020, marked the 100th year anniversary of the advent of, the now proclaimed potentially most useful, tidal energy technology,20

From 2015 through 2019, “approximately $22 billion were reported as invested in geothermal energy by 53 countries”.21 When one sees that over 50 countries, in a five year period, collectively invested only approximately 10% of what Qatar did for the 2022 World Cup, one realizes that football appears to be a higher priority than is investing in natural, free clean geothermal energy.

Planting a seedling tree costs approximately one dollar US. 22 Planting one trillion trees could avert a disastrous climate change scenario, while providing numerous economic, social and ecological benefits. 23 Thus, for just more than one sixth of the 2020 annual global governmental fossil fuel subsidies, and for slightly less than 1% of the 2022 103 Trillion dollar GDP 24, the world could plant enough trees to establish a nature-based, risk free, ecologically positive foothold on securing a sustainable future for all, while ensuring human rights based security through a vast investment in global natural capital, and also while providing employment.

At the same time, Carbon Capture and Storage can help bridge gaps in the carbon balance. Carbon sequestration technologies work within the carbon paradigm, to allow continued carbon based socio-economic development to more gently transition to cleaner energy sources with far less carbon restricting measures which negatively affect billions of people. Carbon Sequestration offers a buffering to the socio-economic and cultural stresses related to rapid decarbonizing the world, stresses which are likely to continue to be, more pressing for those less advantaged. Figure 1 cross compares the different types of energy, and ways to save energy, with key socio-economic and ecological issues. Qualitative data assessed through an extensive literature review was made more robust by a simple ranking system. Additionally, seven professionals in sustainable development reviewed the data and generally agreed with the generalized findings.25 Although detailed discussion about this data is beyond the scope of this paper, the reader is welcome to review the self-explanatory matrix below to see how it more robustly reflects the many points brought forth in the essay. Figure 2 in the following section, illustrates how CSS fosters human rights, broadens people choices and supports basic human needs and values platforms.

| Figure 1: A Systems Approach to Thinking Critically about Energy Options | |||||||||||||

Legend: -2 MORE NEGATIVE, -1 NEGATIVE, 0 NEUTRAL OR N/A, 1 POSITIVE, 2 MORE POSITIVE, ? UNKNOWN | |||||||||||||

| Fossil Fuels | Nuclear | Hydro | Bio-mass Bio- Gas Bio- Fuels | Wind | Solar Photo- Voltaic | Geo- thermal /steam | Wave/ Tidal/ Ocean Thermal | New Green Tech/ other energy forms | Solar Passive/ Thermal /Green Building | Animal/ Human Power | Material/ energy/ food saved and not wasted | Carbon Capture, use and Storage (CCS) | |

| CREATING ENERGY | SAVING ENERGY | CAPTUR-ING AND STORING ENERGY | |||||||||||

| Eco- systemic impact | -2 | -2 | 0 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| High cost to build and maintain infra- structure | -2 | -2 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | -1 |

| Local environ- mental. issues | -2 | -2 | 0 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Accidents/ frequency | -2 | -1 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Impact of accidents -social | -2 | -2 | -1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Impact of accidents -economic | -2 | -2 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Impact of accidents on global eco- system | -2 | -2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Impact of accidents on local environ-ment | -2 | -2 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Renewabil-ity of resources | -2 | -2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Working for global green energy transition | -2 | -2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Fuel for intensive use/ industry | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | -2 | -2 | 1 | -1 | ? | -2 | -2 | -2 | 0 |

| Tech options for individual citizen off-grid | -2 | -2 | -1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | -2 | -2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Vulner-ability to terrorism | -1 | -2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Vulner-ability to natural disasters | -2 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Eases a rapid decarboni-zation | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Economic investment in In situ infra-structure | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -1 | -1 | -2 | -1 | -2 | -2 | -2 |

| Public sector/ governing bodies support in words | -2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | -2 | 2 | -2 | -1 | -2 |

| Public sector/ governing bodies support in subsidies/ lobbying2627 | 2 2021 USD 5.9 Tril | 2 2019 USD 1.9 Tril | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -2 | -2 | 1 | -2 | -2 | -2 |

Carbon Sequestration: Bridging the Carbon Transition within a Human Rights Paradigm

Mary Hoff, in “Eight Ways to Sequester Carbon to Avoid Climate Catastrophe.” EcoWatch, Ensia, Oct. 2021, introduces categories of carbon sequestration. These include afforestation, and reforestation, encouraging the correct mix of plants to maintain carbon negative status, and carbon farming, which “uses plants to trap CO₂, then strategically uses practices such as reducing tilling, planting longer-rooted crops and incorporating organic materials into the soil, to encourage the trapped carbon to move into—and stay in—the soil”.28 Also included are bioenergy and bury which converts biomass into a usable energy source, and then it captures and concentrates it, and traps it into rock formations. Carbon-rich Biochar, made from crop waste, has been used for hundreds of years to enrich soil for farming, but it has recently gained popularity due to its ability to sequester carbon. Rock solutions refer to using large quantities of carbon capturing minerals such as olivine to absorb CO₂, yet practical challenges remain cumbersome, while direct CO₂ capture from air, known as direct air capture and storage remains an embryonic, although promising, technology. 29

Wetlands are important natural capital assets because they absorb atmospheric carbon and reduce carbon loss, which affects long-term storage. They can be managed as a natural response to climate change. Wetlands are important ecosystems because they provide habitat, biodiversity, and aquatic balance. Global wetland research studies demonstrate how environmental management can increase carbon sequestration while improving wetland function.30

Mikunda, Tom, et al. in “Carbon Capture and Storage and the Sustainable Development Goals.” International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control, Elsevier, Apr. 2021, details how carbon capture and storage (CCS) can help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. The author notes that CCS is a key enabler of Goal 13 relating to combating climate change. Also noted is that CS also enables provision of affordable energy and decarburization of industry. The conclusion of this article was that “none of the inhibiting impacts identified had ‘cancelling’ interactions against the SDG’s covered in this assessment”. Of utmost importance, it also noted that CS is a “sustainable option to combat climate change and does not prohibit the achievement of any other SDG”.31

Olabi, A.G., et al. in “Assessment of the Pre-Combustion Carbon Capture Contribution into Sustainable Development Goals SDG’s Using Novel Indicators.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Pergamon, Oct. 2021, considers the role of Carbon Capture (CC) in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The indicators have nine main benefits, i.e., provide information, benchmark sustainability performance, improve risk management, enhance data management and reporting practices, improve resource allocation and reduce the expenses, improve environmental performance, reduce social impact, and improve communications with stakeholders.”32

Most importantly, only CCS enables significant additional decarburization in energy-intensive industries. Iron and steel, as well as chemicals, cement, and refineries, are all energy-intensive industries. The majority of the options for reducing emissions in these sectors have already been implemented (primarily through increased energy efficiency). Since CO₂ is produced by both processes and fuels, only CCS allows for significant additional decarbonization in industry.

Figure 2 below cross examines the various forms of biotic CSS and aspects of human-rights based sustainable development. Using a cross comparison matrix, although seeming pedantic with almost all cells marked, allows no escape from clearly seeing how sequestrating carbon, by simply protecting and conserving what humanity was gifted by nature, meets all human needs and values. Until humanity has done all they can to support these nature-based ways to sequestrate carbon, governments and citizens should not support strict and life hindering carbon based restrictions.

| Figure 2 Matrix showing how types of biotic carbon sequestration which help some of the most disadvantaged people, foster human rights and developmental values, increase basic needs platforms and widen peoples’ choices. All these activities are low cost, low technology and widely accessible. All activities do not need to involve governments. | ||||||||

| Types of Biotic Carbon Sequestration | ||||||||

| Afforestation/ Reforestation | Wetlands Preservation | Planting mixed specialty crop varieties Eg. hemp | Maintain Boreal Forests | Maintain Tropical Forests | Maintain Tropical Savannahs | Maintain Ocean Health | Maintain Mangroves | |

| Human Needs and Values | ||||||||

| Freedom from servitude | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Freedom from oppression | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Adequate food | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Adequate water | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Adequate wood and plant based materials for human use | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Building Natural Capital | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Increasing animal habitat | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Strong Communities | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Adequate nature based medicines | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Maintain knowledge of traditional medicines | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Environmental well being maintained | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Psychological well being maintained | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters rural work | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters rural living | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Allows less dependence on governments | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Preventing rural – urban migration | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Employment for rural youth/other increased | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Increasing peoples choices | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Maintains culture for rural peoples | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Maintains culture for Indigenous peoples | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provides employment | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Provides skills training | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters cooperation and sharing | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters critical human connection to Cosmos, Nature, Others and Inner Self | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters right to a free and fair world | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Helps poor communities help themselves | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Fosters self- reliance for food and fuel | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Species preservation and proliferation | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Ecosystem function fostered | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Food Chains protected | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Maintains soils | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

Conclusion

In 1990, two years before the dawn of UNFCCC, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), in its first Human Development Report, defined sustainable human development simply as “both the process of widening people’s choice and the level of their achieved well-being”. 33 Since then in the decades that followed, the UN system and partners regarded a human-rights based approach to development as the way to proceed with the betterment of humankind. Following the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was foundational, prior to the design and onset of any developmental activities. This was well understood. In direct opposition to UNDP’s definition of human development, much of rapid decarbonization will indeed be about lessening, and not widening, people’s choices.

As we look at the issues embracing the politics behind our changing climate today,

we see that we have indeed meandered from the more ideal politics, to a sort of pseudo politics. The outcome of this long and arduous journey, serves neither man nor beast, and now, through ecosystemic collapse, even threatens humanity, as evidenced by the cross analysis presented. The other eight million- or so- species with whom we share this planet, unseen, and unheard, given neither the smallish shred of right nor glory, will merely be considered as collateral damage.

We see today, political systems reflecting tendencies towards a merger of economy and state and this business-smart form of governance has proven to lay fertile ground for an even further distillation of the wealthy few, and for the wealth of the Commons to serve not its people, but a small and exclusive group of interests. What is called for are truly democratically run climate-smart, survival-smart forms of business and governance, within societies, where both social and eco-systemic concerns remain as center-point, and where basic human needs and rights, are met without vast disparity, within a society where sustainable principals operate, and where the stockpiling of surplus, and obvious displays of great material wealth, are considered passé.

In sum and in conclusion, it is seen that CSS is an excellent option to allow a slower transition to a balanced emissions global economy, while maintaining the vital human rights based foundation to all that is sustainable development. However, until the money matches “the talk”, and until the near six trillion dollars per year of subsidies are stopped, the half trillion dollars per year fostering alternatives will continue to be unheard cries in the wind. The technologies have been here for decades and continue to evolve albeit with little financial support. The UN and other international dialogues have been advocating greening energy since the 1970’s. At the end of the day, and all things considered, the takeaway is, that it is all about money, and money connected to politics and information, and it truly is, as simple as that.

Bibliography

Aarol B, Admin. “Hundreds of Civil Society Organizations Worldwide Denounce World Economic Forum´S Takeover of the UN – Friends of the Earth International.” Friends of the Earth International, 2 Oct. 2019, www.foei.org/hundreds-of-civil-society-organizations-worldwide-denounce-world-economic-forums-takeover-of-the-un.

Analytics, Mega Trends. “Over $22 Billion Have Been Invested in Geothermal Energy During 2015-2019 – REGlobal -.” REGlobal, 15 May 2020, reglobal.co/over-22-billion-have-been-invested-in-geothermal-energy-during-2015-2019

Alkire, Sabina. “Introducing the Human Development and Capability Approach.” OHPI United Nations, 4 Mar. 2021, www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ssAlkire-Deneulin_Ch2.pdf.

All Rights Reserved, 2022 International Monetary Fund. “Fossil Fuel Subsidies.” IMF, 7 Mar. 2021, www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies#:~:text=Globally%2C%20fossil%20fuel%20subsidies%20are,generally%20larger)%20continues%20to%20climb.

Barnes, Angela. “Trading Tidal Energy.” Capital, 8 Mar. 2021, capital.com/trading-tidal-energy-time-to-invest-in-europe-s-surging-wave-power.

Buotte, Polly. “Carbon Sequestration and Biodiversity Co-benefits of Preserving Forests in the Western United States.” ESA Ecological Applications Association, 3 Feb. 2021, esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/eap.2039.

Buss, Wolfram, et al. “Enhancing Natural Cycles in Agro-ecosystems to Boost Plant Carbon Capture and Soil Storage | Oxford Open Climate Change | Oxford Academic.” OUP Academic, 1 Jan. 2021, academic.oup.com/oocc/article/1/1/kgab006/6317838.

Carrington, Damian. “Tree Planting ‘has Mind-blowing Potential’ to Tackle Climate Crisis | Greenhouse Gas Emissions | the Guardian.” The Guardian, 4 July 2019, www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jul/04/planting-billions-trees-best-tackle-climate-crisis-scientists-canopy-emissions.

CC, Creative Commons. “Corporate Capture of Global Governance: WEF-UN Partnership Threatens UN System | ESCR-Net.” ESCR-Net, 5 Apr. 2018, www.escr-net.org/news/2019/corporate-capture-global-governance-wef-un-partnership-threatens-un-system.

Chami, Ralph. “International Monetary Fund.” International Monetary Fund, 1 Dec. 2019, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2019/12/natures-solution-to-climate-change-chami.htm.

Creative Commons Attribution, -Noncommercial-Share. “Nuclear Energy Institute.” Open Secrets, 22 July 2022, www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/clients/summary?cycle=2019&id=D000000555.

Davis, UC. “Carbon Sequestration | UC Davis.” UC Davis, 31 Jan. 2022, climatechange.ucdavis.edu/climate/definitions/carbon-sequestration.

Gleckman, Harris. “WEF Takeover of UN Strongly Condemned.” WEF Takeover of UN Strongly Condemned, 16 Jan. 2020, www.fian.org/en/press-release/article/wef-takeover-of-un-strongly-condemned-2273.

Gregg, Ruth, and Mike Morecroft. “Natural England Publishes Major New Report on Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Habitat.” Natural England Publishes Major New Report on Carbon Storage and Sequestration by Habitat – Natural England, 20 Apr. 2021, naturalengland.blog.gov.uk/2021/04/20/natural-england-publishes-major-new-report-on-carbon-storage-and-sequestration-by-habitat/.

Guterres, António. “Corporate Capture of Global Governance: The World Economic Forum (WEF)-UN Partnership Agreement Is a Dangerous Threat to UN System | Cognito Forms.” Corporate Capture of Global Governance: The World Economic Forum (WEF)-UN Partnership Agreement Is a Dangerous Threat to UN System | Cognito Forms, 6 Mar. 2021,www.cognitoforms.com/MultistakeholderismActionGroup/CorporateCaptureOfGlobalGovernanceTheWorldEconomicForumWEFUNPartnershipAgreementIsADangerousThreatToUN?fbclid=IwAR0jaqd3fdz2Nl3ndlSl-fbR1mlMwMESKTDX5SlwtN-kwY3eLfQAFq71ujM.

Halprin, Amanda. “Managing Wetlands to Improve Carbon Sequestration – Eos.” Eos, 16 Nov. 2021, eos.org/editors-vox/managing-wetlands-to-improve-carbon-sequestration.

Hoff, Mary. “8 Ways to Sequester Carbon to Avoid Climate Catastrophe – EcoWatch.” EcoWatch, 19 July 2017, www.ecowatch.com/carbon-sequestration-2461971411.html.

ICCP, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “History — IPCC.” History — IPCC, 1 Jan. 2022, www.ipcc.ch/about/history.

Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin, River Basin. “Seedling Tree Planting – ICPRB.” ICPRB, 29 Sept. 2001, www.potomacriver.org/resources/get-involved/water/seedling-tree-planting/#:~:text=The%20cost%20associated%20with%20planting,a%20better%20chance%20of%20survival.

Kowalska, Aneta. “Carbon Sequestration.” Plant–Soil Interactions in Soil Organic Carbon

Sequestration as a Restoration Tool, ScienceDirect Topics, 2020, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/carbon-sequestration.

Lo, Stephanie. “The Forum of Young Global Leaders.” The Forum of Young Global Leaders, 6 Apr. 2021, www.younggloballeaders.org.

Melillo, Jerry. “Soil-Based Carbon Sequestration.” MIT Climate Portal, Apr. 2021, https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/soil-based-carbon-sequestration.

Mikunda, Tom. “Carbon Capture and Storage and the Sustainable Development Goals – ScienceDirect.” Carbon Capture and Storage and the Sustainable Development Goals – ScienceDirect, 10 Apr. 2021, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1750583621000700.

Mohammed, Amina, and Børge Brende. “UN WEF Partnership Framework.pdf | Powered by Box.” Box, 13 June 2019, weforum.ent.box.com/s/rdlgipawkjxi2vdaidw8npbtyach2qbt.

NEF, Bloomberg. “Bloomberg NEF.” Bloomberg, 8 Mar. 2021, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-19/spending-on-global-energy-transition-hits-record-500-billion.

Olabi, A. “Assessment of the Pre-combustion Carbon Capture Contribution Into Sustainable Development Goals SDGs Using Novel Indicators – ScienceDirect.” Assessment of the Pre-combustion Carbon Capture Contribution Into Sustainable Development Goals SDGs Using Novel Indicators – ScienceDirect, 25 Oct. 2021, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032121009849.

Research Population U. “Countries by GDP 2022.” Countries by GDP 2022, 8 Apr. 2022, www.populationu.com/gen/countries-by-gdp.

Sanford, Claire. “Prince Charles COP26 Climate Summit Glasgow Speech Transcript | Rev.” Rev, 18 Sept. 2022, www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/prince-charles-cop26-climate-summit-glasgow-speech-transcript.

ScienceDirect ®, 2020 Elsevier . “Science Direct.” Science Direct Carbon Sequetration, 2 Apr. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032121009849 34.

Stiell , Simon. “Framework Convention for Climate Change.” Framework Convention for Climate Change, 28 Mar. 2021, unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2022_03E.pdf.

TNI, Transnational Institute. “End The United Nations/World Economic Forum Partnership Agreement.” Transnational Institute, 25 Sept. 2019, www.tni.org/es/art%C3%ADculo/pon-fin-al-acuerdo-de-asociacion-estrategica-entre-las-nacione

s-unidas-onu-y-el-foro?content_language=en.

UN, United Nations. “The Paris Agreement.” United Nations Climate Change, 2 Feb. 2016, unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

UN, United Nations. “Homepage | UN Global Compact.” Homepage | UN Global Compact, 22 Sept. 2022, www.unglobalcompact.org.

UN, Framework Convention for Climate Change. “Framework Convention for Climate Change.” Framework Convention for Climate Change PDF, 6 Nov. 2021, unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2021_L14a1E.pdf.

UN, United Nations. “Home | UN Office for Partnerships.” UN Office for Partnerships, 3 Mar. 2019, unpartnerships.un.org.

Vallero, Daniel. “The Carbon Cycle.” Carbon Sequestration – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics,

Fundamentals of Air Pollution (Fifth Edition), 2014, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/carbon-sequestration.

Waring, Bonnie, et al. “Frontiers | Forests and Decarbonization – Roles of Natural and Planted Forests.” Frontiers, 1 Jan. 2001, www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/ffgc.2020.00058/full.

WMO, World Meteorological Organization. “GCOS | WMO.” GCOS | WMO, 6 Feb. 2022, gcos.wmo.int/index.php/en/global-climate-indicators.

1 Davis, UC. “Carbon Sequestration | UC Davis.” UC Davis, 31 Jan. 2022, climatechange.ucdavis.edu/climate/definitions/carbon-sequestration.

2 ICCP, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. “History — IPCC.” History — IPCC, 1 Jan. 2022, www.ipcc.ch/about/history.

3 UN, Framework Convention for Climate Change. “Framework Convention for Climate Change.” Framework Convention for Climate Change PDF, 6 Nov. 2021, unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2021_L14a1E.pdf.

4 UN, United Nations. “Homepage | UN Global Compact.” Homepage | UN Global Compact, 22 Sept. 2022, www.unglobalcompact.org.

5 UN, United Nations. “Home | UN Office for Partnerships.” UN Office for Partnerships, 3 Mar. 2019, unpartnerships.un.org

6 Mohammed, Amina, and Børge Brende. “UN WEF Partnership Framework.pdf | Powered by Box.” Box, 13 June 2019, weforum.ent.box.com/s/rdlgipawkjxi2vdaidw8npbtyach2qbt.

7 Sanford, Claire. “Prince Charles COP26 Climate Summit Glasgow Speech Transcript | Rev.” Rev, 18 Sept. 2022, www.rev.com/blog/transcripts/prince-charles-cop26-climate-summit-glasgow-speech-transcript.

8 Lo, Stephanie. “The Forum of Young Global Leaders.” The Forum of Young Global Leaders, 6 Apr. 2021, www.younggloballeaders.org.

9 Gleckman, Harris. “WEF Takeover of UN Strongly Condemned.” WEF Takeover of UN Strongly Condemned, 16 Jan. 2020, www.fian.org/en/press-release/article/wef-takeover-of-un-strongly-condemned-2273.

10 CC, Creative Commons. “Corporate Capture of Global Governance: WEF-UN Partnership Threatens UN System | ESCR-Net.” ESCR-Net, 5 Apr. 2018, www.escr-net.org/news/2019/corporate-capture-global-governance-wef-un-partnership-threatens-un-system.

11Guterres, António. “Corporate Capture of Global Governance: The World Economic Forum (WEF)-UN Partnership Agreement Is a Dangerous Threat to UN System | Cognito Forms.” Corporate Capture of Global Governance: The World Economic Forum (WEF)-UN Partnership Agreement Is a Dangerous Threat to UN System | Cognito Forms, 6 Mar. 2021,www.cognitoforms.com/MultistakeholderismActionGroup/CorporateCaptureOfGlobalGovernanceTheWorldEconomicForumWEFUNPartnershipAgreementIsADangerousThreatToUN?fbclid=IwAR0jaqd3fdz2Nl3ndlSl-fbR1mlMwMESKTDX5SlwtN-kwY3eLfQAFq71ujM.

12 TNI, Transnational Institute. “End The United Nations/World Economic Forum Partnership Agreement.” Transnational Institute, 25 Sept. 2019, www.tni.org/es/art%C3%ADculo/pon-fin-al-acuerdo-de-asociacion-estrategica-entre-las-nacione

s-unidas-onu-y-el-foro?content_language=en.

13 Aarol B, Admin. “Hundreds of Civil Society Organizations Worldwide Denounce World Economic Forum´S Takeover of the UN – Friends of the Earth International.” Friends of the Earth International, 2 Oct. 2019, www.foei.org/hundreds-of-civil-society-organizations-worldwide-denounce-world-economic-forums-takeover-of-the-un.

14 UN, Framework Convention for Climate Change. “Framework Convention for Climate Change.” Framework Convention for Climate Change PDF, 6 Nov. 2021, unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2021_L14a1E.pdf.

15 UN, Framework Convention for Climate Change. “Framework Convention for Climate Change.” Framework Convention for Climate Change PDF, 6 Nov. 2021, unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sbi2021_L14a1E.pdf.

16 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, 2022 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. “Fossil Fuel Subsidies.” IMF, 7 Mar. 2021, www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies#:~:text=Globally%2C%20fossil%20fuel%20subsidies%20are,generally%20larger)%20continues%20to%20climb.

17 NEF, Bloomberg. “Bloomberg NEF.” Bloomberg, 8 Mar. 2021, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-19/spending-on-global-energy-transition-hits-record-500-billion.

18 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, 2022 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. “Fossil Fuel Subsidies.” IMF, 7 Mar. 2021, www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies#:~:text=Globally%2C%20fossil%20fuel%20subsidies%20are,generally%20larger)%20continues%20to%20climb.

19 Barnes, Angela. “Trading Tidal Energy.” Capital, 8 Mar. 2021, capital.com/trading-tidal-energy-time-to-invest-in-europe-s-surging-wave-power.

20 Barnes, Angela. “Trading Tidal Energy.” Capital, 8 Mar. 2021, capital.com/trading-tidal-energy-time-to-invest-in-europe-s-surging-wave-power.

21Analytics, Mega Trends. “Over $22 Billion Have Been Invested in Geothermal Energy During 2015-2019 – REGlobal -.” REGlobal, 15 May 2020, reglobal.co/over-22-billion-have-been-invested-in-geothermal-energy-during-2015-2019

22 Analytics, Mega Trends. “Over $22 Billion Have Been Invested in Geothermal Energy During 2015-2019 – REGlobal -.” REGlobal, 15 May 2020, reglobal.co/over-22-billion-have-been-invested-in-geothermal-energy-during-2015-2019

23 Carrington, Damian. “Tree Planting ‘has Mind-blowing Potential’ to Tackle Climate Crisis | Greenhouse Gas Emissions | the Guardian.” The Guardian, 4 July 2019, www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jul/04/planting-billions-trees-best-tackle-climate-crisis-scientists-canopy-emissions.

24 Research Population U. “Countries by GDP 2022.” Countries by GDP 2022, 8 Apr. 2022, www.populationu.com/gen/countries-by-gdp.

25 Professionals worked in UNDP UNEP World Bank FAO and UNICEF, and all were Senior Professionals.

26 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, 2022 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. “Fossil Fuel Subsidies.” IMF, 7 Mar. 2021, www.imf.org/en/Topics/climate-change/energy-subsidies#:~:text=Globally%2C%20fossil%20fuel%20subsidies%20are,generally%20larger)%20continues%20to%20climb.

27Creative Commons Attribution, -Noncommercial-Share. “Nuclear Energy Institute.” Open Secrets, 22 July 2022, www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/clients/summary?cycle=2019&id=D000000555.

28 Hoff, Mary. “8 Ways to Sequester Carbon to Avoid Climate Catastrophe – EcoWatch.” EcoWatch, 19 July 2017, www.ecowatch.com/carbon-sequestration-2461971411.html.

29 Hoff, Mary. “8 Ways to Sequester Carbon to Avoid Climate Catastrophe – EcoWatch.” EcoWatch, 19 July 2017, www.ecowatch.com/carbon-sequestration-2461971411.html.

30 https://eos.org/editors-vox/managing-wetlands-to-improve-carbon-sequestration

31 Vallero, Daniel. “The Carbon Cycle.” Carbon Sequestration – an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics,

Fundamentals of Air Pollution (Fifth Edition), 2014,

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1750583621000700 33

34 ScienceDirect ®, 2020 Elsevier . “Science Direct.” Science Direct Carbon Sequetration, 2 Apr. 2019, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032121009849 34.

33 Alkire, Sabina. “Introducing the Human Development and Capability Approach.” OHPI United Nations, 4 Mar. 2021, www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/ssAlkire-Deneulin_Ch2.pdf.